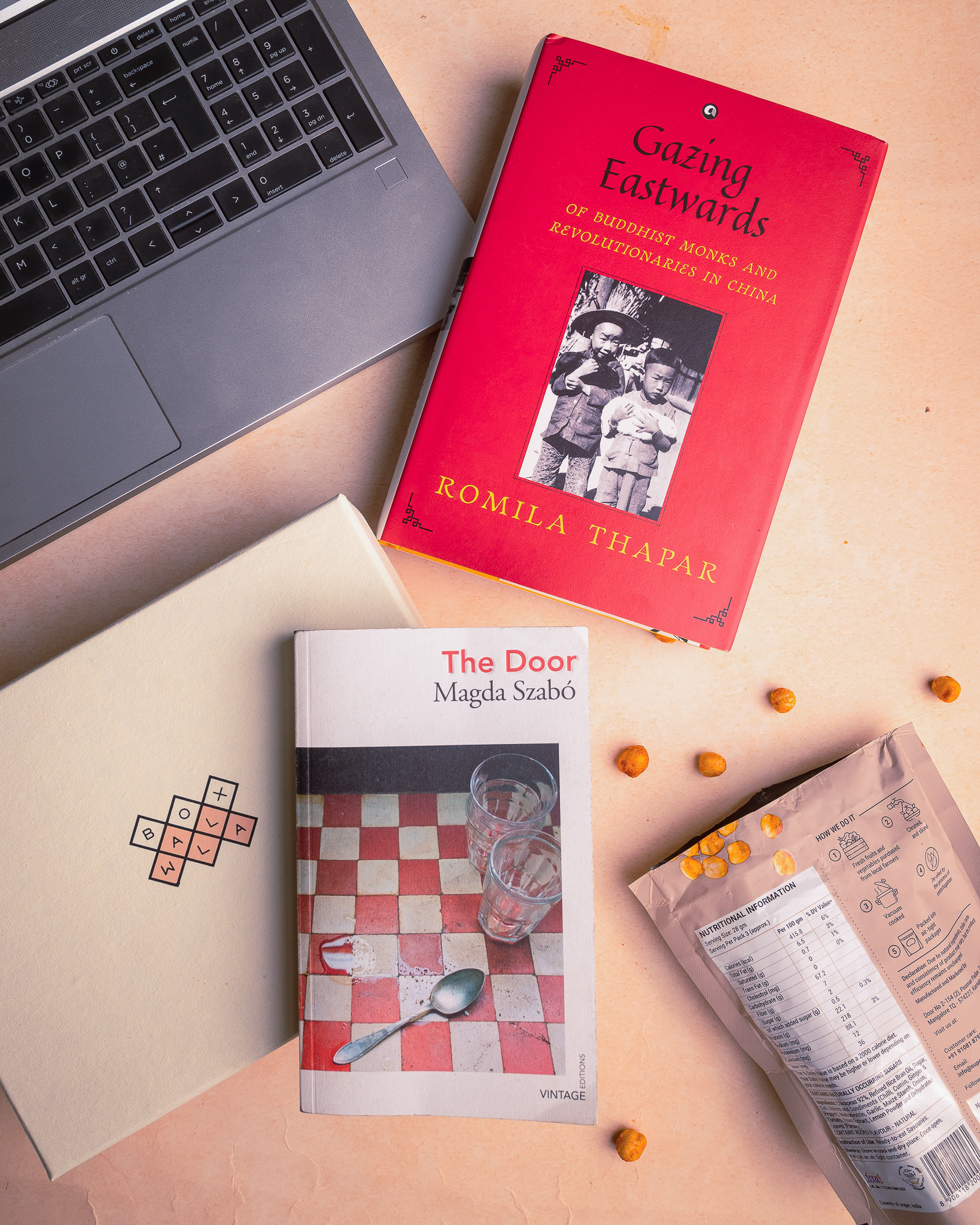

Maybe there is something wrong with me, but it feels so much easier to share why I don’t like something than why I do. It’s even worse when I love something … I find myself repeating the same three or four words about it, like a toddler talking about their favourite TV show. Even then, to say I love The Door by Magda Szabo feels like an understatement. I did not know when I picked up this slim, unassuming book that it would become something so beloved, a heavy but precious weight on my soul. I knew when I was reading it that I would be rereading it in the future, and my thoughts will change, and I will find deeper meanings and more reasons to love this novel. This realization filled me with both dread and excitement, like all great books do. The Door is a story I will never forget.

So you can maybe understand why I’ve been putting off publishing this. (Thank you Lavanya and Sandeep for your incredible patience.) I’ve been writing and rewriting, though mostly abandoning what I wrote. Whatever I say does not seem to capture how incredible this book is. Who am I to say anything, anyway? Here I try, one final time, to push everyone to read The Door.

The Opening of The Door: The Plot Is Revealed, the Reader Hooked

Consider the extracts below, from the first chapters of two other incredible books:

The first line of Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s Chronicle of a Death Foretold contains a spoiler for the whole novel:

“On the day they were going to kill him, Santiago Nasar got up at five-thirty in the morning to wait for the boat the bishop was coming on. He’d dreamed he was going through a trove of timber trees where a gentle drizzle was falling, and for an instant he was happy in his dream, but when he awoke he felt completely splattered with bird shit.”

Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier begins with a dream that haunts every page:

“Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again.”

The chapter ends with a spoiler: Manderley is no more. You can feel all of the narrator’s longing and unspoken regrets, a sense of an irrevocable ending. The past, which can never be lived again, feels more real and important than the present:

“In reality I lay many hundred miles in another country and would wake in a little while, in a bare little hotel room. The sky would be bright and glittering, so different from the soft moonlight of my dream. The day would lie before us, long and uneventful perhaps, but filled with a peace we had not known before. We would not talk of Manderley. I would not mention my dream, for Manderley was no longer ours. Manderley was no more.”

Now, consider how The Door starts:

“I seldom dream. When I do, I wake with a start, bathed in sweat. Then I lie back, waiting for my frantic heart to slow, and reflect on the overwhelming power of night’s spell. As a child and young woman, I had no dreams, either good or bad, but in old age I am confronted repeatedly with the horrors of my past…”

This first chapter also ends with a spoiler, with regret, with longing:

“I killed Emerence. The fact that I was trying to save her rather than destroy her changes nothing.”

We know nothing about the author here, or Emerence. But it is clear that they had a deep, intimate relationship, which ended with Emerence’s death. The novel is about this relationship, and we know it is over and why it is. Then, why do we keep reading? Books that begin with endings are usually bleak, and we watch on with horror and fascination as mistakes occur and everything changes. But we cannot look away, we cannot stop reading. Our lives too have regrets, relationships that ended years ago but continue to haunt us, people we miss terribly though their memories seem to mock us. We’ve seen how sometimes, words spoken in a moment can shatter a bond that had endured for years. We know the comfort we’ve felt when we formed connections with people, and the intense loneliness that hits when a misunderstanding or silence threatens these relationships.

We read these stories because from the first chapter, we recognize the feelings that the narrators cannot rid themselves of. We are here to listen to their story, and to everything they aren’t saying. We know these narrators may not be blameless or reliable; but neither are we. We dread the ending even though we know what will happen. These stories endure because they are human. And in The Door, you can feel that Magda Szabo has shared her deepest, most human parts of herself with us.

Is the Narrator Magda Szabo?

But why do I say Magda Szabo? Surely, it is the narrator and not the author itself. But the similarities between the author and the narrator, who is unnamed except when she is called a nickname, are too many to ignore.

Magda Szabo (1917–2007) was born in Debrecen, north-eastern Hungary. She was raised in a devout Protestant and intellectual family where Szabo’s father taught her to converse in German, English, Latin, and French. After graduating from the University of Debrecen as a teacher of Latin and of Hungarian, she taught classics at a Calvinist girls’ school. In 1945, she began working in in the Ministry of Education. Two years later, she married Tibor Szobotka, a writer and translator of James Joyce and George Eliot, among others.

Szabo began her writing career as a poet, during which time she came in contact with the New Moon Group, who defined poetry of that generation in Hungary. Her second collection, Back to the Human, was awarded the Baumgarten Prize, one of Hungary’s most prestigious literary awards. However, the award was taken away the same day as Szabo was declared an enemy of the people by the recently installed communist party. She was fired from the Ministry the same year. During the Stalinist rule of Hungary, she was not allowed to publish her work. Banned from publishing, Szabo turned to fiction, defying the guidelines of Social Realism laid down by the State and writing about what she referred to as “terrible women”.

In The Door, the narrator is also a writer whose works for years have been censored by the Communist government. The novel opens when she is finally receiving recognition again. In fact, she hires Emerence to take care of her housework because her and her husband have more work now. When she receives an important prize that gives her even more recognition and work, is Szabo alluding to the Baumgarten Prize she received? Szabo wrote the novel a few years after her husband’s death. The narrator’s husband in The Door is sick, and she cares for him with Emerence. In interviews, Szabo has suggested that this novel is a “thinly veiled personal history.”

This presence of the author in the text makes the story feel even more personal and confessional in nature. Though Szabo doesn’t reveal much about the narrator in the novel, even though door after door is opened to reveal more parts of Emerence, her writing feels too honest and real to be only fiction – or maybe that is what the best of fiction is. Whatever the case, I hope you don’t mind that I refer to the narrator henceforth as Magda.

Magda and Emerence

When Magda first meets Emerence, she of course has no idea how much this old woman will mean to her, and how their relationship will span two decades. The household help-employee power dynamic can never be equal. Emerence and Magda are also opposites of each other in most ways. Emerence is a practical, anti-intellectual woman of almost superhuman strength. She does an extraordinary amount of physical labour in the neighbourhood. She is also an eccentric: nobody is allowed into her house, her past is a mystery, her moods are unpredictable, she has an uncanny connection with animals.

The power dynamics in their relationship may seem inverted – it is Emerence who interviews Magda before she decides to work for her; only Emerence is allowed to give gifts or take care of Magda and never vice versa. Magda often feels Emerence has more control in the relationship – you can feel her frustrations with Emerence refusing to let her into her home and her life, her hurt she is when Emerence mocks her work and her thoughts. Whenever Emerence refuses her help or if her attempts to help backfire, she is even more determined to be useful, as Emerence is to her.

Her persistence seems to pay off. Emerence reluctantly opens the doors Magda keeps pounding, and the women develop a relationship – whether it a friendship, an intimacy, or a relationship born out of need (on Magda’s side) or weariness (on Emerence’s). Female friendships are intense yet fragile. For many women, these are their deepest bonds. The end of such a relationship can feel more traumatizing than a romantic breakup. Emerence becomes a larger-than-life figure in Magda’s life. Though they are so vastly different from each other, they are also drawn to the other. The Door feels like a dream, an epic, an allusion at times. It is a novel where seemingly nothing happens, and yet we are felt with anticipation and dread, happiness and terror.

Emerence: The Enigmatic Centre of the Story

The Door is, in many ways, the book most synonymous with Szabó’s work, particularly its concerns with the ways in which national history inform the politics of subjectivity, class, and intergenerational relationships.

– K. Thomas Kahn, Magda Szabó’s “The Door”, Words without Borders

The reading of The Door as a story of female friendship works only as long as we ignore Emerence’s interiority. And we cannot ignore Emerence, for she is the centre of the book, and a perpetually haunting figure in the author’s life, even after her death.

Magda may operate on the belief that Emerence and her are on an equal footing, but it is clear they are not. Magda is shocked when Emerence interviews her before agreeing to work for her. She is not used to providing references for herself; nor does it occur to her that someone who will work at her home may have good reasons to vet her too. Though Emerence and Magda are from the same region, the former has nothing, while the latter is descended from a lineage of important and intellectual people. The book has many instances of Magda lying down, sleeping, thinking, writing. In contrast, Emerence is working even on Christmas Day. They are never equals, but can they be friends? If they can, will such a friendship endure? How can we answer this without knowing who Emerence is?

Is Emerence enigmatic because we only know her through the narrator’s words – a narrator who rendered unreliable because of her intimate relationship with her subject. Is Emerence going to forever be a ghost haunting her life? Is she an allegory for Hungary’s past? Is she a receptacle for all the guilt Magda feels, all the regrets we have in our own relationships? Or is she simply an old woman trying to get by, whom the author has imbued with such deep meaning? Whoever she is, why does she haunt us too?

If you’ve received this Book Box, you know what Claire Messud has said about this novel. I leave you with another quote from her:

“If you’ve felt that you’re reasonably familiar with the literary landscape, ‘The Door’ will prompt you to reconsider.”

We’d love to hear what you have to say about The Door by Magda Szabo. It is the fixed book in our first-ever India Book Box. If you would like to subscribe to our Book Boxes, you’ll receive two incredible books every two months. Come read with us, and let’s talk about our shared loves and pains.