One of the options in our first ever Boxwalla India Book Box is the latest novel by Percival Everett, one of our old favorite of ours. If you choose Book Box 2, you are in for a treat: you will receive Magda Szabo’s The Door, and James by Percival Everett. Both books tell extraordinary stories: this box is perfect for those who love a good (dare we say, great) novel – or two.

An Introduction to James, by Percival Everett

Before we start, I have a disclaimer: To call James a retelling or reimagining of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn doesn’t quite do justice to this extraordinary new novel by Percival Everett. The best description of the book is by Everett himself:

Here, I will not be reviewing the novel; I do not want to spoil anything. Enough to say that I absolutely loved this book; in fact, it is my favorite Percival Everett novel so far. On the other hand, I had only a faint recollection of Huckleberry Finn, having read an abridged version as a child. The story left no impression on me, and I read no more Twain. All I could remember about Jim was that he a perpetually obliging and cheerful companion to Huck. Still, I was struck by the contrast between Twain’s Jim and Everett’s James.

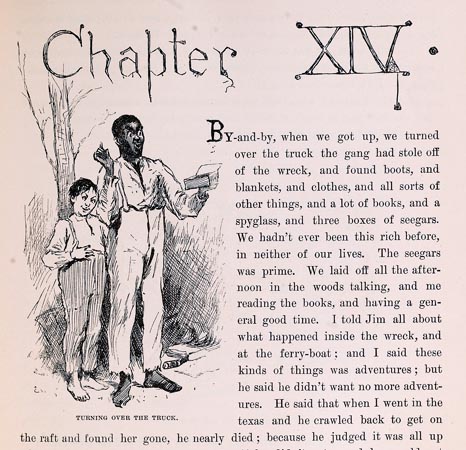

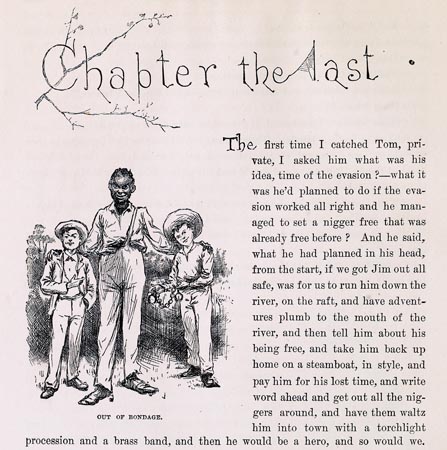

James, however, is not a character in some book I will soon forget. Honestly, it feels like a disservice to call him a character. A few weeks have passed since I finished the book, but James still feels like a living, breathing person to me, and I find myself momentarily worrying about how he is doing. I read everything I can find about James before I began reading up about how Mark Twain depicted Jim in Huckleberry Finn. By the time I saw the illustrations of Jim in the first edition of the book, I had to concede that though James is no mere retelling of reimagining of Twain’s novel, we cannot ignore Twain or Huckleberry Finn. If for nothing else but to see how beautiful and heartbreaking a character and story Everett managed to create from the caricature of a person that is Mark Twain’s Jim.

A Short, Simplified Summary of the Reception of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn was published in the United Kingdom in December 1884 and in the United States in February 1885. It is considered to be one among the Great American Novels. Since its publication, the book has been both cherished and criticized. The first major work of American literature to be written in vernacular English, employing regionalisms and local usage, it was criticized upon its release for its “coarse” language. Several American libraries banned it upon publication. However, Twain already had developed a reputation as a humorous writer, and some controversy was expected.

It was only later that Twain and his works became the subject of enduring debates for his depictions of race. While many Twain scholars have argued that Huckleberry Finn attacks racism by humanizing Jim and poking holes in the logic of racist assumptions. However, others argue that Twain was unable to rise above the racist stereotypes of his time and only reinforced them in his depiction of Black people in the book, especially Jim. One cannot also ignore the number of times racial slurs are used in the book.

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn remains one of the most banned books in the US; it also remains popular among readers.

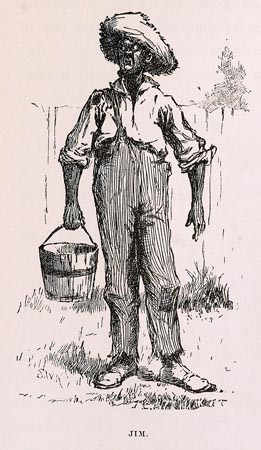

Jim in Illustrations from the First Edition of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

The picture of a little boy being stung by a bee in Life magazine caught Mark Twain’s eye. He asked his relative, Charles L. Webster, whom he had set up with a publishing house, to hire the cartoonist to illustrate his latest work, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. The illustrator was E.W. Kemble. In his words, this is how he got the job:

“Casting about for an illustrator, Mark Twain happened to see this picture. It had action and expression, and bore a strong resemblance to his mental conception of Huck Finn. I was sent for and immediately got in touch with Webster. The manuscript was handed me and the fee asked for–two thousand dollars–was graciously allowed. I had begun drawing professionally two years before this date, and was now at the ripe old age of twenty-three.”

– “Illustrating Huckleberry Finn” by E.W. Kemble

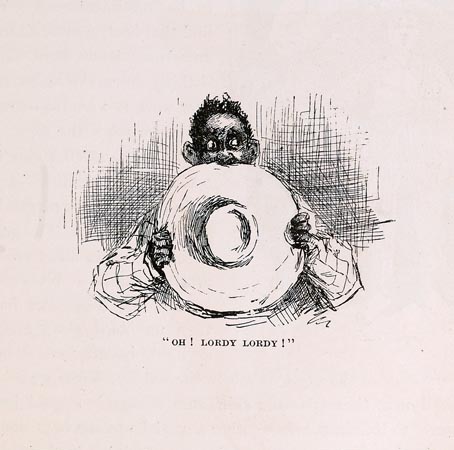

While Twain tried to (whether successfully or unsuccessfully is contentious) subvert racist stereotypes, Kemble’s images employed stereotypes – racist ones – to depict the Black characters in Huckleberry Finn. Kemble’s illustrations had a huge influence on how readers would picture the characters of the book, especially since Twain hadn’t provide detailed physical descriptions for them in the text. In this context, it is important to see how Sawyer and Kemble’s contemporaries (and they themselves, we could say) would’ve pictured Jim. Kemble’s illustrating process for Jim is revealing. He used the same model, a young boy, as a model for all the images in the book:

“I used my young model for every character in the story–man, woman and child. Jim the Negro seemed to please him the most. He would jam his little black wool cap over his head, shoot out his lips and mumble coon talk all the while he was posing.”

– “Illustrating Huckleberry Finn” by E.W. Kemble

Images credit: Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. (Tom Sawyer’s comrade). By Mark Twain. With one hundred and seventy-four illustrations. New York, Charles L. Webster and Company, 1885. SPECIAL COLLECTIONS: PS1305 .A1 1885c: Copy 1: Original pictorial green cloth. Numerous newspaper clippings pasted inside both covers. Gift of Dr. Wilbur P. Morgan of Baltimore. Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia. All rights reserved. See all of Kembe’s illustrations here.

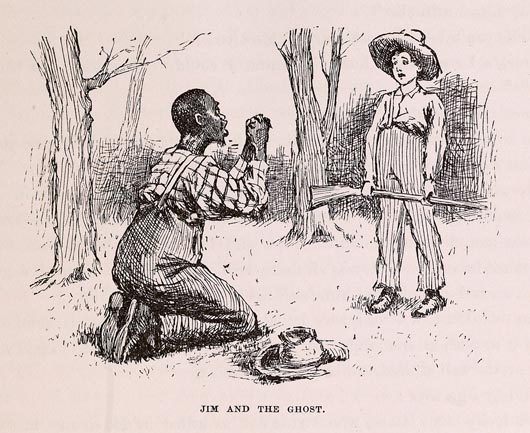

Matthew Teutsch has a great article on Interminable Rambling about Kemble’s illustrations. The article is a good read in its entirety, and here I am quoting some of what Teutsch says about the image below:

…where did Kemble’s images come from? For one, they came from minstrel shows. However, as Stephen Railton notes on Mark Twain in His Times, they also came from other sources, most notably possibly from Josiah Woodbridge’s abolitionist image of an enslaved man kneeling and asking, “Am I not a man and a brother?” In Chapter VIII, Huck discovers Jim on Jackson’s Island. In the illustration, we see Jim kneeling, with his hands clasped, in a similar manner to the enslaved man in Woodbridge’s image. The difference, though, is the presence of Huck. Jim’s position, in a subservient pose to Huck, presents him as inferior to the fourteen-year-old Huck. As well, Huck holds a gun in his hands. Railton points out the power dynamics at play in the image: “Most readers want to see the meeting on Jackson’s Island as the beginning of a friendship, but as the visual starting point for their life together, this illustration draws a pretty blunt picture of the power dynamics between the races.”

– Matthew Teutsch, “Illustrations in ‘The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn’”

Twain himself reviewed Kemble’s paintings, and Kemble went on to be sought out for his “Negro type” illustrations. For an overview of how Jim was illustrated over the years, click here.

James: A “Dismantling of that Shopworn Staple”

“James is best understood as a systematic dismantling of that shopworn staple, the Black man or woman who exists to rescue and morally enlighten a fallen but basically redeemable white protagonist. And Everett’s quarrel is not with this archetype alone. He takes aim at the ethics embodied by the magical Negro: the idea that oppression exalts, that suffering purifies the spirit. Everett’s counter-thesis is that oppression hardens; suffering sharpens. James cuts.”

– “A Bloody Retelling of Huckleberry Finn“, The Atlantic

In Huckleberry Finn, Jim is a kind, superstitious, loyal man, free of self-interest, cheerful and cooperative as Finn’s sidekick. Though his presence is the reason Huckleberry comes to realize that slaves are people like him, that is all that Jim is in Mark Twain’s novel: a medium for the main character’s growth. James, however, is no Jim. He is a thinker, a reader and writer. In his narrative, he isn’t a naturally suppliant being grateful for his master’s benevolence, but a sharp, thoughtful man trying to protect himself, as much as he can in a world where he has no power. He is an atheist, though around white folks, “Oh, Lawdy Lawd, we’s be believin’.”

Twain is considered to have revolutionized American literature by using vernacular English in his novel. Huckleberry Finn is the narrator, and the language he uses is of an uneducated, poor child. How faithful is his depiction of Black people, of the enslaved characters in his book? Twain drew from minstrel shows, from existing depictions and stereotypes of Black people in his writing. Finn has a memorable arc as he finds it increasingly difficult to align his learned prejudice with the love he feels towards Jim; he is a fully fleshed out character. Jim, reliable and one-dimensional, exists in the book for Huck to prove his character.

James is a real person, Everett insists in every page of his novel. The world he occupies is also all too real, with deadly consequences.

James, Percival Everett, and Language

Any reader of Percival Everett knows his deep fascination with language, especially how language has been and is used to depict Black people. This is especially evident in Erasure (now a major motion picture American Fiction) where, as an angry joke, Thelonious “Monk” Ellison writes an outrageous, stereotypical, racist depiction of a Black convict. Much to Ellison’s chagrin, this book attracts the rave attention that his academic, philosophical writings never received. Everett’s characters live very much in the real world: under white eyes, they are either too Black or not Black enough. Blackness is a performance, though the audience are impossible to convince.

In James, much of he humor and irony is derived from language, in adding another layer to Twain’s use of it too. James shares his author’s interest in the workings of language. Twain’s Jim is a mask that James wears in Everett’s novel. He code-switches when talking to white people, and teaches enslaved children how to do so. “Safe movement through the world depended on mastery of language, fluency,” he knows with a painful certainty.

However, Everett would not be Everett if he stopped at inverting the character of Jim; his fascination and expertise goes beyond Twain’s. James is no mirror image of Jim, a pool of coolness and rationality guided by his moral codes. The world of slavery is not the world of reason. James argues with Locke, with Voltaire, with Rousseau, but the absurdity of it all eliminates reason:

“How strange a world, how strange an existence, that one’s equal must argue for one’s equality, that one’s equal must hold a station that allows airing of that argument, that one cannot make that argument for oneself, that premises of said argument must be vetted by those equals who do not agree.”

The Weight of a Pencil

James follows the same trajectory as Huckleberry Finn until around halfway of the book. Huckleberry’s tale of daring adventure becomes, in James’s voice, a journey with deathly consequences. It is as if Everett picks up every event in Twain’s novel and stretches it until the story expands to reveal how unfair and tragic it actually is. Once you hear Jim’s voice, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn can only be a tragedy.

But James and Huckleberry Finn are not the same stories. Everett is done working with Twain’s story. Many reviews describe James as full of Everett’s trademark wit and irony, but all the jokes, the masks, the ironies, debates about equality and little moments of love, levity, laughter, all are subsumed by the very real dread that James feels: that he can be captured or killed any day. James is a horror story in many ways. James can no longer fit Twain’s world. Everett’s James is a legend, his name evokes fear and hope by the time the novel ends. He is shocked at how powerful anger can feel, and soon, it drives him forward. His anger grows quietly and steadily as he repeatedly endures the violence and senselessness of his world. At times, his anger has explosive consequences.

The bodies, tragedies, and consequences add up. Everything feels heavy, like it can be a reason to kill. James does not have the privilege to not see. Under his gaze, inconsequential everyday things for most of us today have life-and-death consequences. Each word James writes has the weight of a life. His pencil is the heaviest thing in the world, even if it makes him lighter. Everett refuses to look away. James refuses to accept.

Get this Book Box here.